It doesn’t seem possible my 30th high school class reunion is fast approaching. Surely, I’m not old enough for this to be happening. When I think back to high school, I think of my orange and black pom-poms, long, bumpy bus rides to speech contests, and spinning on stage in a teal blue skirt during a swing choir performance.

In high school, nothing is more important than your image and my high school experience was no different. My appearance meant everything to me. Each night before school, I would pick the perfect outfit from my closet to wear the next day. I lived in Carroll, a town of almost 10,000, but I had the latest styles from the big city of Des Moines. For a time, my dad lived there, and my brothers and I would visit him. We would beg our dad to take us to Valley West Mall so we could walk around and ogle the latest trends. We wanted whatever was new in the fashion world. My oldest brother, Doug, likened me to Imelda Marcos for my love of shoes and Lisa Bonet for my love of hats.

It was one of my many hats that caught the attention of a local photographer. He was a family friend who often used our large backyard with massive evergreen trees for photo shoots. I was attending a high school basketball game when he saw me wearing a black wide-brimmed hat, most likely from The Limited. He asked me if I would be interested in posing for a few photos for an upcoming photography contest. As an attention-loving 15-year-old, I quickly agreed and set out to find the perfect wardrobe.

I settled on a burgundy silk shirt and that smart black hat. At the time, I had braces, which made it a bit awkward to pose for pictures, but I tried my best to work around them. I had a lot of fun with the photo shoot. I asked my best friend, Kari, to come along to be my “stylist.”

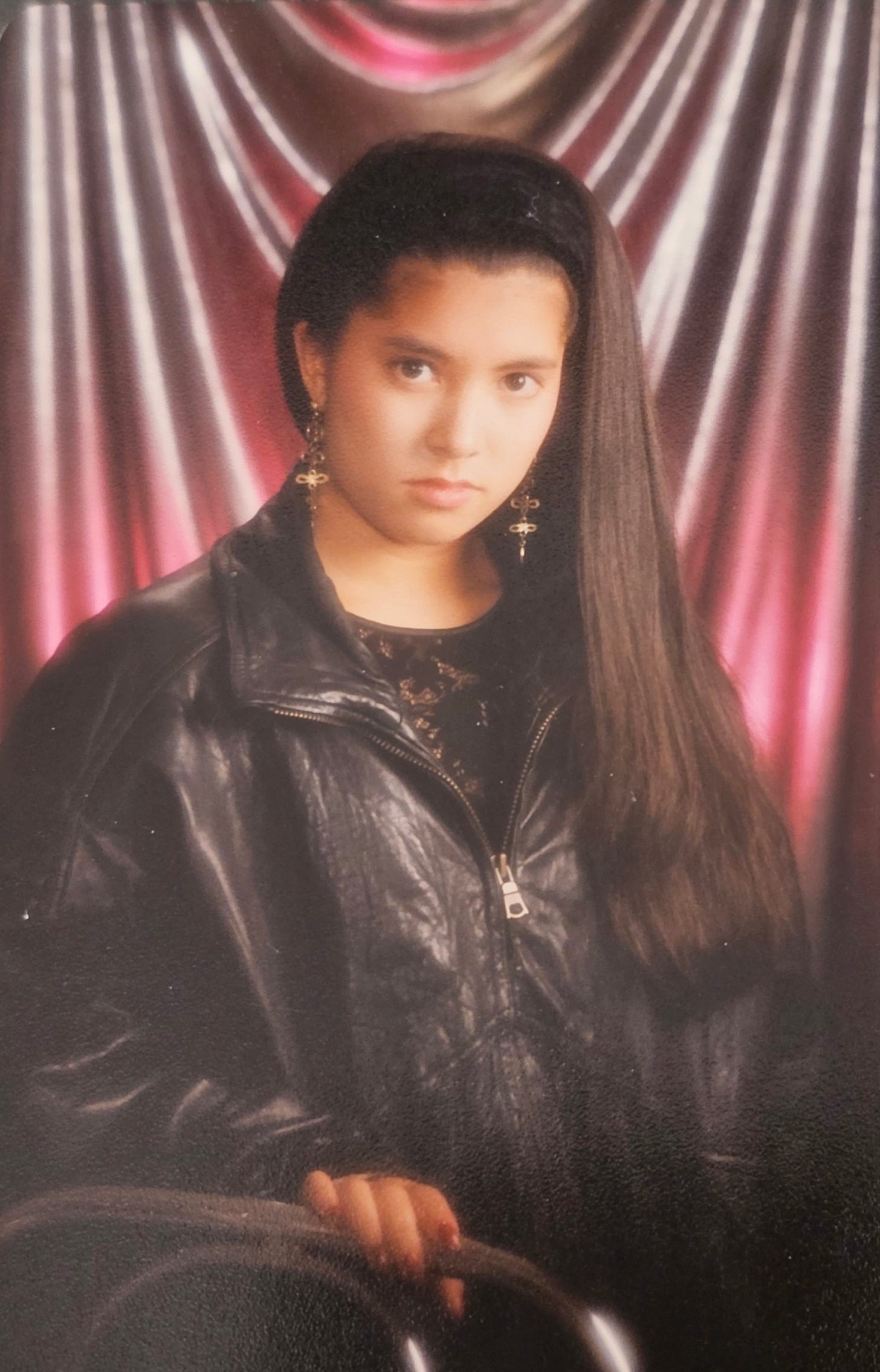

The next year, the photographer, Eric Nicewanger, asked if I would be willing to pose for another set of photos. This time, I included an edgier look in my modeling wardrobe. I settled on my brother Tom’s black leather jacket, a lace top, and a velvet headband. By this time, my braces were off, and I was able to pull off a more serious look. The photo print ended up placing in the contest.

Eric showed me a snapshot of my print entitled, “Sweet Rebellion,” hanging in the photography exhibition at Epcot Center and I felt grown up and very special.

During my junior year, I was running laps in PE in the school gym. A senior boy ran past me and out of nowhere, he called out, “Go back to the rice paddies, you f^&%ing Jap.” I was stunned. From where did this come? Looking back, maybe that student was taking U.S. History at the time, I have no idea. I had never had a run in with this boy in the past. I remember telling the PE teacher what the boy said to me. I don’t remember if the teacher said anything to the boy, but I know there were no repercussions. Back then, bullying was considered to be something more physical than mental. That incident was a cruel reminder that I was different than my peers. On the inside, I felt the same, but I knew on the outside, I stuck out like a sore thumb.

My senior year came and went. I was busy with a whirlwind of activities. I ended high school on a high note. I was selected for Individual All-State Speech. I settled on the University of Iowa and thought I was ready to tackle college in Iowa City. I had about ninety students in my graduating class, most of whom I had known since kindergarten or even preschool. In high school, I was known for leading the pep rallies and donning the latest trends. After I left high school and my hometown, no one knew me. I soon discovered I didn’t know who I was to myself or anyone else.

When it was time for me to attend my university orientation, I chose not to listen to my mom about not staying out too late the night before. She woke me up bright and early the next morning. I had only been asleep for a few hours. I got dressed and got into the car for the three-hour car ride to Iowa City. I’m pretty sure I slept most of the way there. When we arrived, we were greeted by a cheery college student. She handed us name tags, an itinerary, and a map of the campus. We sat down to listen to someone from the university welcoming us to orientation. I glanced around at the other students’ itineraries. My schedule included something about Multicultural Student Support. I wasn’t sure what that meant, but I was to walk to the student union and go to a room on the second floor. After the welcome speech by the university, I headed over there on my own. It was a strange feeling to have such independence. It was the fall of 1993, and I was almost 19 years old.

I entered the Iowa Memorial Union, looked at a map, and walked up a set of stairs. There it was. A sign hanging on the outside of the room read, “Welcome Multicultural Students.” When I saw the sign, I froze. I knew what the sign meant, but there was something inside of me that felt uneasy about opening the door and going inside. My entire life, I knew I wasn’t white, but I grew up in an all-white family and all of my friends were white. It’s hard to explain, but strangely, I felt white on the inside even though I know I wasn’t white on the outside. When I looked in the mirror and saw myself, I saw someone with dark eyes, black hair, and tan skin. In my head, I knew I wasn’t white, but somehow, I felt like I was almost another “version” of white.

I stood nervously outside the door. I peeked into the room through a small window. I saw students with dark hair and various shades of skin tones sitting in chairs listening to the speaker. I held out my arm to turn the doorknob, but I pulled my hand back. “Not yet,” I told myself in my head. I waited a few more minutes and took a breath, gathered my courage, opened the door, and stepped into the room. All eyes turned to me. I could no longer deny my identity. I was a multicultural student and this is where I was supposed to be.

I felt like by walking in that door, I was letting go of believing I was something I wasn’t. Was I ready to face the next four years?